[tweetmeme source=”cchibwana” only_single=false]

Going through my old files, I found this article which I did way back in September of 2004. It appeared in The Nation newspaper of 28 September 2004. Note that I haven’t updated it so some information might be outdated, but it’s worth reading.

CAN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES BENEFIT FROM THE WORLD TRADE ORGANISATION?

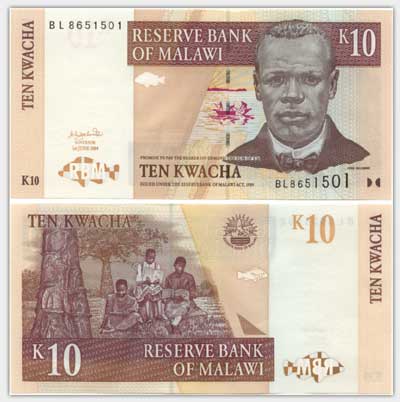

The World Trade Organization (WTO) replaced the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1995. The three main objectives of the WTO are to help trade flow as freely as possible, to achieve further liberalisation gradually through negotiation, and to set up an impartial means of settling disputes on trade. Its main purpose is thus to promote free international trade. Compared to GATT, the WTO is much more powerful because of its institutional foundation and its dispute settlement system. Member countries that do not abide by the WTO’s trade rules are taken to court and can eventually face retaliation. The 134 countries members of the WTO have had to adapt their national legislation to the rules of the WTO. The most powerful members of the WTO are USA, the European Union (EU), Japan and Canada. Developing countries are the majority in number (2/3), but not in power. Malawi joined the WTO on 31 May 1995.

Historically, GATT enforced phased-in tariff reductions worldwide up until the Uruguay Round (1994). The trade negotiations focused on non-agricultural goods, mainly because the U.S. wanted to protect its farm sector. As the corporate interests of the developed countries have expanded, they have lobbied for an incorporation of more issues into the GATT/WTO. Its agenda now includes agriculture, services (financial, telecommunications, etc.), intellectual property rights, and electronic commerce.

Theoretically, the WTO is a democratic body, and all WTO members have an equal voice, but in practice, the WTO is still a way from being fully democratic, and poor countries are subject to bullying unlike at the UN. Decisions at the WTO are made behind the scenes, as countries trade concessions with one another and naturally this horse-trading favours those countries with a lot of financial & political power. Rich countries, particularly the US, EU, Japan and Canada, have well funded teams of specialist negotiators at the WTO headquarters, while half of the poorest countries in the WTO can’t afford even one and, in addition rich countries have been known to use intimidation and threats to get their way.

The least developed countries (LDCs) are less likely to benefit from the WTO because they are marginalized in the world trade system, and their products continue to face tariff escalations. US and other industrial countries have exorbitant textile tariffs which constitute big barriers to the export of textile and clothes from Africa (Zimbabwe, Zambia, Uganda, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Malawi), one of the sectors where these countries could be competitive. Washington has promoted free trade principles only in sectors that benefit the U.S. economy; in other sectors, like textiles, protectionism reigns.

While at the UN, the principle is “one nation one vote”, this is not the case at the WTO, where the big countries are the real “decision-makers”. Within the WTO framework, developing countries have less power and influence because although they make up 75% of WTO membership and by their vote can in theory influence the agenda and outcome of trade negotiations, they have never used this to their advantage. Most developing country economies are in one way or another dependent on the U.S., the EU, or Japan in terms of imports, exports, aid, etc. Any obstruction of a consensus at the WTO might threaten the overall well-being of dissenting developing nations. Trade negotiations are based on the principle of reciprocity (or “trade-offs”) i.e. one country gives a concession in an area, such as the lowering of tariffs for a certain product, in return for another country acceding to a certain agreement. This trade-off benefits only the large and diversified economies, because they can get more by giving more. Negotiations and trade-offs therefore take place among the developed countries and some of the richer or larger developing countries. Sub-Saharan African countries have fewer human and technical resources. Many cannot cope with the 40-50 meetings held in Geneva each week. Hence they often enter negotiations less prepared than their developed country counterparts.

Africa has very little saying and on top of it, it has not the means to participate fully in all the discussions in the working groups in Geneva, because it lacks the economic and technical fibre. Only 26 out of the 39 African countries have a permanent ambassador in Geneva, and only Uganda has an ambassador specially attached to the WTO. Even the countries having ambassadors in Geneva they can hardly follow all that is going on at the Geneva WTO Centre.

Under the WTO, use of subsidies in production is discouraged so that all countries have a level playing field. Subsidies help reduce the cost of production to the producer and this implies a relatively lower output (and selling price) is required to break-even. However rich countries use subsidies to support their own large companies and traders while poor countries have been forced to reduce the protection that they can give their own producers. Both the European Union and the United States protect and subsidise their agricultural producers, encouraging production of large surpluses of food while there are no such subsidies for the smallholder producer in Malawi. The African market is often flooded with European or USA food dumped products (sold at a price lower than its real value because they are subsidised by their governments). These lowers prices threaten local production of food as local producers cannot compete in these conditions. A country’s staple crop production can be easily devastated by an influx of cheap imports. Trade liberalisation can cause deterioration of farmers’ life standards and influence negatively food security. Small producers in poor countries are increasingly expected to compete with large scale, technically advanced, subsidised producers on the world market. Removing subsidies that lead to dumping of cheap exports in poor countries is certainly beneficial and the UK Government deserves credit for having pushed for this in the EU.

The rich countries claim that the WTO is helping the world move towards a system of ’free trade’ in which every country will specialise in producing what it’s good at, and everyone will benefit. They claim that if all countries play by the same rules, this will be fairer for all, but in such an unequal world, this kind of trade would be far from fair. It would be like a football match between Manchester United and the local Bunda Socials FC – there might be a level playing field, but Manchester United will still win each time the two sides clash.

For African countries, a change in the EU farm policies e.g. by eliminating subsidies, would benefit them far more than all the EU aid programs to help poor countries. Africa could also benefit from processing its agricultural products, but the barriers to imports in industrial countries make it difficult to export them. The EU and the USA fear competition, and thus keep their trade barriers for processed food.

There is little or no evidence to support claims that free trade lifts people out of poverty and, in fact, there is much that indicates to the contrary. Such countries that have rapidly opened their markets to free trade, as Mali and Zambia, have very poor records of economic growth and poverty reduction. On the other hand, South East Asian countries, which have successfully reduced poverty through trade, did not use free trade policies. Some of the policies they used (such as restrictions on investments by transnational companies, selective protection of imports, and flexibility on patents) would not have been allowed under current WTO rules.

According to the IMF, sixteen sub-Saharan African countries have lower trade barriers than the EU, yet these countries are struggling to improve living conditions for their people. As Nelson Mandela observed, rules uniformly applied to WTO members have brought about inequalities because each member has different economic circumstances. The WTO should therefore put poor people and the planet first, rather than apply the same rules to all countries regardless of their specific needs.

For most poor producers, local markets are far more important than international markets. Poor producers do not have a realistic chance of benefiting from foreign markets, so it is very important that they can sell their produce locally other than focus on the international market fantasy. African firms and farmers are small and lack the technology and marketing skills to compete in the world market. The opening of markets has mainly benefited the transnational corporations at the expense of national African economies and the small farmers, workers, and jobless persons.

Economic theory suggests that protectionism enhances growth of infant industries. If poor countries’ industries are to reach the standards and productivity required to benefit from international trade, then they need the support of their governments and require a protected local market in which to grow. Many developed countries used government intervention in the past to develop their own industries, but the UK Government is trying to make it difficult for poor countries to follow the same course.

In countries such as Zambia and Malawi, where 85% of people depend on farming for their living, millions of farming families don’t have electricity, piped water, adequate housing, or money for shoes, medicines, school fees and sometimes even food. Poor farmers, who lack tools, transport, capital to buy seeds, and even proper roads to reach markets, simply can’t compete equally with agri-businesses in rich countries. Poor countries need special treatment to protect their agricultural sectors and small-scale producers.